fangirl (/ˈfanɡəːl/): a female fan, especially one who is obsessive about comics, film, music, or science fiction. I bet I can predict what pops into your mind when you come across this word. Mile-long queues outside concert venues, the air of teenage expectation intoxicating the air, hundreds of high-school girls shrieking, fainting, and crying, chasing after the newest leather-clad heartthrob.

Teenage fangirls have been mindlessly demeaned, degraded and dismissed for decades. The 40s’ Bobby Soxers – young American girls between the ages of twelve and eighteen, categorised by their white, ankle-length Bobby socks – marked a shift in the popular consciousness, establishing the idea of modern fan culture for the first time. Despite being the masterminds behind a massive movement of teenage revolutionaries, these girls were named by major publications as “mindless worshipers of Frank Sinatra or crazed followers of adolescent fads”.

Fast-forward twenty years, and the Beatles have taken over the globe. This perplexing social phenomenon dubbed “Beatlemania” seemed to possess fans, namely teenage fangirls, leading them to carry out senseless and hysterical acts. Notable occasions include creating a four-mile-long traffic jam at an airport or shattering twenty-three windows and a plate-glass door (summer of 1964, the Beatles visit Miami). Ringo Starr, the band’s drummer, remarked feeling like “something in a zoo” after having a lock of his hair nicked as a souvenir by a Washington fangirl.

At the turn of the millennium, the 2000s marked a new period in the history of the fangirl. The introduction of social media allowed fans to have 24-hour access to their objects of worship. Online platforms such as Tumblr or Twitter became safe havens for fandom groups, creating a space solely designated for discourse, speculation, and mutually enabled obsession over favourite celebrities or media.

Thousands of communities sprout out of thin air: Beliebers, One Directioners, Potterheads, Arianators (the list truly is endless). With their newfound ability to congregate in highly organised groups, fangirls start to standardise their roles and make things happen with their “power in numbers”. Guidelines are drawn out. To be a true fan, one must memorise a set list of trivia, participate in group activities – concert projects, streaming parties, hashtags – and perform fanhood in a specific, correct way. This, which used to be constrained to individual admiration, had now evolved into a community practice and maybe even a way of being.

The fundamental rules of economics show time and time again that when a successful business opportunity presents itself, it will be swiftly taken advantage of. The rise of fandom culture brought attention to the sheer consumer power of teenage fangirls, a market that had been previously relatively unexplored despite having considerable financial potential for corporations and artists alike. There is an unholy amount of money to be made in this industry: merch, events, meet-and-greets, concerts, albums, vinyls, collectables, brand collaborations, and so on.

An artist whose name has become nearly synonymous with discussions about the economic power of fandoms is pop powerhouse Taylor Swift. Her “Eras Tour” kicked off in March of this year and has since then sold out countless arenas on several different continents. This tour has made headlines due to its unprecedented financial success: Swift herself is reported to be taking home around 10 to 13 million dollars per tour stop. However, Taylor Swift is not the only one reaping the financial benefits of her thriving Eras Tour: for every 100 dollars spent on the concert itself, fans are estimated to be individually spending 1,300-1,500 dollars on additional services, mostly sourced from the local area the shows are being held in. Each performance of the Eras Tour is raking up two to three times the amount of revenue for local businesses as a Superbowl.

This tremendous economic impact has not gone unnoticed. J. B. Pritzker, the governor of Illinois, recognised Swift for reviving tourism in the state after her three-night performance in Chicago. Additionally, the Federal Reserve has credited her Eras Tour for significantly boosting the American tourism industry.

It is clear to see that the impacts of fan culture are not at all confined to the digital space. Why is it, then, that the role of the fangirl is so consistently dismissed and reduced to a sort of teenage quirk? I offer an explanation: an observable societal trend that points to the lower cultural value attributed to things associated with or dominated by females.

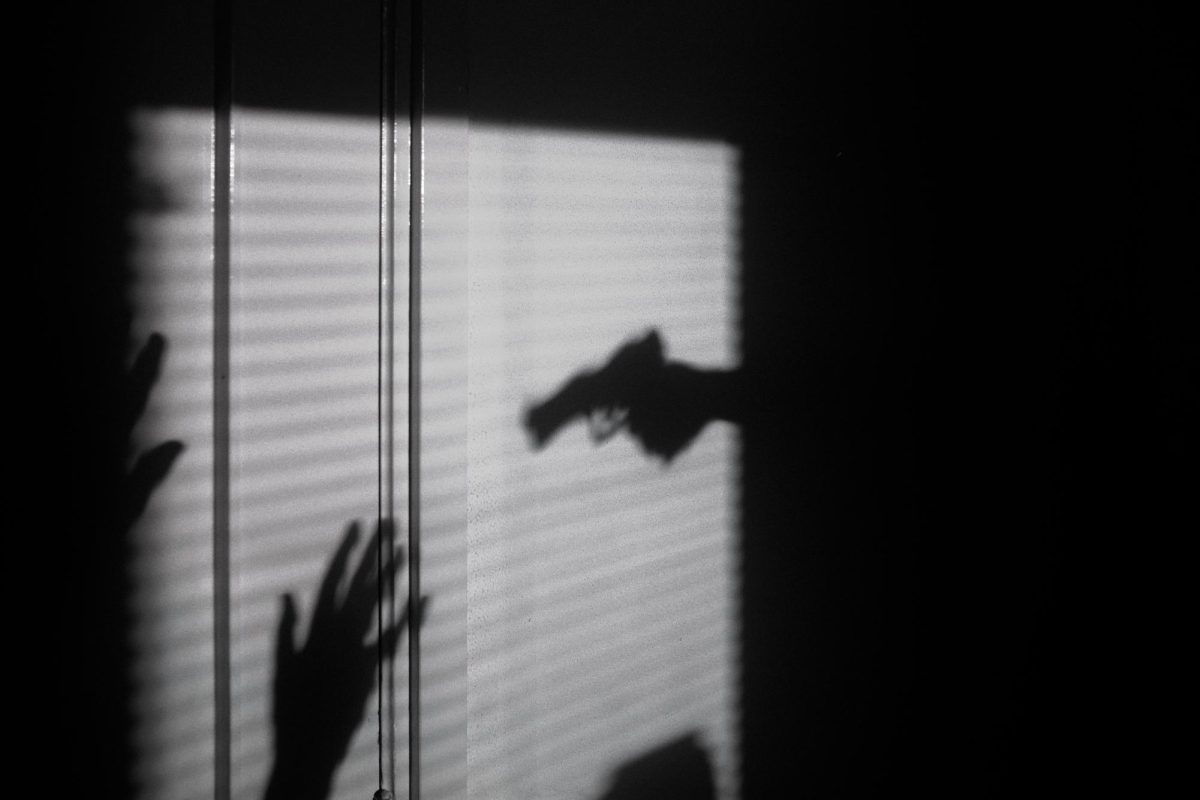

To demonstrate my point, I will draw a comparison between fans of sports teams and fans of celebrities, two areas with highly contrasting gender demographics. It is a true statement that fangirls might behave in an over-the-top and maybe even hysterical manner when in the presence of their idols. However, it is also true that sports fans are known not to be the most level-headed or tranquil group, especially when faced with their team’s defeat or other unfavourable outcomes. Instances of sports spectator violence during events – excluding riots or fights outside the competitions themselves, which, I would argue, are where most of the violence takes place – are numerous and date back all the way to the 1800s.

If this pattern of behaviour is seen within both fangirls and sports fans (and arguably, even more intensely on the side of the latter), why is it that only one group has a negative social stigma intrinsically attached to it? I would claim that, despite this being a very nuanced discussion, a major reason stems from their stereotypical demographics: mainly teenage girls versus men from all walks of life.

Teenage girls, and to a certain extent, women in general, are stereotypically seen to be more emotional than men and to have less control over said emotions. It is logical that, due to this, we as a society would then tend to equate such grandiose emotional performances from different genders with different levels of severity (in terms of social unacceptability). However, there are many unseen positive sides to the culture of fangirls that are fully unappreciated and misunderstood.

It is a significantly positive thing for young people to have an outlet within which to express themselves and their developing personalities. It is even more beneficial for them to have others to connect with who share the same interests as they do. In online spaces, for example, teenagers who do not have the chance to connect socially in person (which may be so due to a myriad of factors, from health status to bullying) have the opportunity to do so on the internet and, given that this is approached in a safe and responsible manner, to take part in an essential step of their mental development into an adult.

The moral nature of the fangirl is a terribly complex and nuanced idea that could be infinitely torn apart and socially analysed. However, I ask of you, the reader, to reconsider your stance on this issue and reflect on where your thoughts might stem from. I can assure you that the Beliebers deserve a lot more social credit than you might have thought to award them before.