In the aftermath of the 2024 United States presidential election, speculation has been rife over whether Donald Trump’s narrow victory over Kamala Harris constituted an electoral realignment, on par with elections such as those of 1932, 1968, and the congressional elections of 1994. Proponents of the realignment theory point to Donald Trump’s impressive margins among working-class and non-college-educated voters, historically Democratic constituencies, and his surprising gains among young and minority voters, particularly Asian and Hispanic voters. These demographics were assumed to comprise the core of the modern Democratic Party; now, that loyalty is in question. Opponents of the theory contend that economic concerns and the global anti-incumbent trend among the working class are responsible for the deviation from normal patterns.

If 2024 really was a realignment, it would mark the end of the Sixth Party System, generally denoted as being in effect since the 1980s, and open a new age of political uncertainty. This article is an explanation of the voting shifts that took place in 2024, and an attempt to predict how these shifts might determine the future political outlook for the United States.

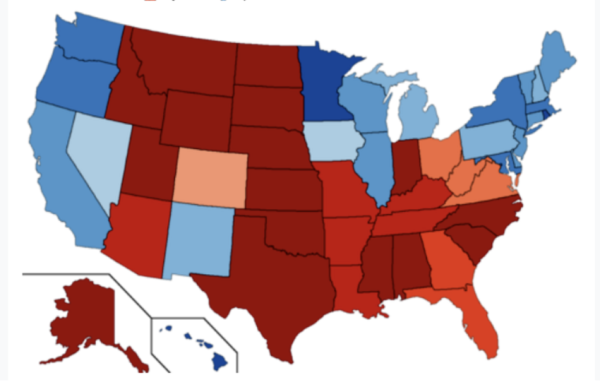

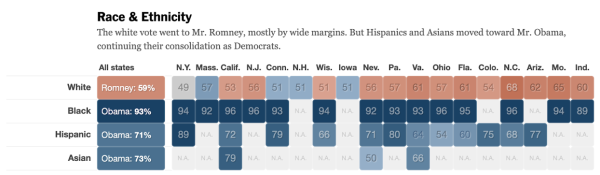

In the Sixth Party System, Democrats dominated in the Northeastern and Upper Midwestern regions of the United States, and by 2008 developed a strong advantage in the Pacific States. Republicans, on the other hand, found their base in the South, the Great Plains, and the Mountain West. These patterns were mostly determined by the presence of large, Democratic-voting urban centers in coastal states, as well as heavy union presence in the Northeast and Midwest, giving the Democrats a large base of white blue-collar voters. In demographic terms, Republicans maintained a solid hold on the white vote, while Democrats won the Black vote by massive margins and carried other minorities by lesser margins.

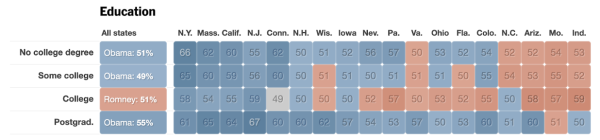

In terms of educational attainment, Democrats regularly won voters with no college degrees or with two-year degrees, while Republicans won voters with four-year degrees. Democrats swept those with postgraduate degrees, a relatively small portion of the overall population.

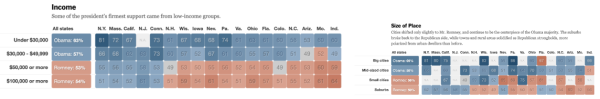

Republicans further won those with higher incomes and those living in rural areas, while Democrats swept working-class voters and city-dwellers. Rural areas, especially ones with mostly white populations, have been shifting towards Republicans since the 1990s, but Obama maintained a decent showing indoors in these areas. Suburbs remained the closest geographical battleground, but with a slight Republican advantage, relative to the nation as a whole.

In the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, some expected long-term shifts continued. Asian and Hispanic voters coalesced around the Democratic Party (with a slight slippage in Biden’s margins from Clinton’s) while urban and suburban dwellers shifted strongly to the left, offsetting continual Republican gains among rural voters. However, the rightward shift among white rural voters spread to white working-class voters, leading to 2016 Republican gains in ancestral Democratic strongholds like Scranton, Pennsylvania (23 points rightward from 2012 to 2016), Flint, Michigan (19 points towards the Republicans), and Duluth, Minnesota (18 points). Trump’s gains in these white, industrial areas handed him his surprise sweep of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. At the time, Hillary Clinton overperformed Obama’s numbers in some “collar counties” around major cities. Examples include Pennsylvania’s Chester County (8 points towards Clinton), Georgia’s Cobb County (9 points to the left), and Wisconsin’s Waukesha County (6 points). In 2020, Joe Biden recovered some of the Democrats’ lost ground in post-industrial cities but didn’t come close to recovering Obama’s 2012 margins. However, 2020 continued the leftward shift of suburbs and urban areas, with most suburban counties swinging leftward by considerable margins.

On the state level, Hillary Clinton overperformed Obama in 11 states and the District of Columbia. These states were Idaho, Utah, Kansas, Texas, Arizona, Virginia, Georgia, Washington, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, and California. These states are disproportionately concentrated in the South and West, signaling a blue shift in those regions. Additionally, many of these states have rich, highly-educated populations, such as Massachusetts and Maryland, demonstrating the leftward shift of these voters, many of whom have been turned off by Trump’s deviations from traditional Republican doctrine. In 2020, despite losing the popular vote by 4.5 points, Donald Trump improved his margin in six states and the District of Columbia. These were: Utah, Florida, Illinois, California, Arkansas, and Hawaii. Two of these states reveal little: Utah’s massive swings in 2016 and 2020 were due to Mitt Romney (the Republican 2012 candidate)’s Mormonism, as well as the presence of a Mormon independent, Evan McMullin, on the 2016 ballot. Arkansas’s shift was probably due to a lingering home-state effect from Hillary Clinton’s time as First Lady of Arkansas. However, Florida, Illinois, California, and Hawaii reveal emerging Republican inroads. In Florida and Hawaii, Trump’s overperformance came off the backs of gains among Cuban and Filipino voters, respectively, foreshadowing Democratic losses among the broader Hispanic and Asian populations. In California and Illinois, Democratic losses were concentrated in cities—possibly due to Democratic slippage among urban, minority, and working-class voters.

In the 2024 presidential election, these emerging trends came to a head. Since the nation swung by around 6.5 points in total to Donald Trump, and he improved his margin in every single state, today’s trends can be examined not by the raw shifts in state or county margins, but by their shifts relative to the nation. By this measure, the places where Republicans notched their greatest improvements were highly-populated states like New York (11 points towards Trump), New Jersey (11 points), California (9 points), and Florida (11 points). These Republican gains came primarily from urban and minority voters, especially Hispanics. Majority-minority Democratic bastions such as Miami-Dade County in Florida or Passaic County in New Jersey, which used to vote for Democrats by 20-point margins, flipped to Trump this election. While the Black vote barely swung towards Trump, his massive gains in the Hispanic vote, narrowing the Democratic margin to six points, grant Republicans an unparalleled opportunity to take advantage of America’s fastest growing demographic group. However, Republicans may have already maximized their gains in white, rural areas: Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin, all heavily, white, rural states, shifted rightward by considerably less than the nation as a whole.

Kamala Harris lost votes from 2020 across the country, but made a few gains in certain counties. These include tourist counties such as Door County in Wisconsin or Cook County in Minnesota, as well as the suburban rings around Denver and Milwaukee. Harris saw the biggest swings in her favor in the outer suburbs of Atlanta, where Henry County gave her her biggest gain, a 9-point swing in her favor from 2020. Harris’s endurance here bodes well for Democrats’ hopes to pull Georgia permanently into the blue column. In demographic terms, Harris only improved on Biden with college-educated white women, while holding the line with other college-educated voters and slipping considerably among the working-class and young voters, particularly men. By income, the vote is inverted from 2012: Harris won higher-income voters while losing the middle and working classes, only winning those making under $30,000 a year. By geography, Democrats still won cities by overwhelming margins, although their numbers decreased somewhat from 2020. Rural areas were won by Trump with massive margins, and suburbs remained divided.

The overall trends point to a future where the Democratic Party wins higher-educated suburbanites, while Republicans sweep the working class and minority voters are divided. It’s not entirely clear who this change will benefit more; the emerging Republican coalition comprises a majority of the country, but the voters coming into the Democratic camp are more likely to turn out, especially during midterms and special elections. It’s also unclear whether the two parties will respond to the interests of their new coalitions. For example, will Republicans become friendlier to unions to court their new working-class base? Will Democrats embrace harsher criminal justice policies to court suburban voters? The face of U.S. politics may be changing, but much is yet to be determined.