I was 13 years old when I watched Eraserhead, David Lynch’s debut feature. In the past I had understood movies as a form of entertainment like any other, an escape from the mundanities of daily life, but not much else. Eraserhead fascinated me. It had no interest in being palatable and certainly not in being enjoyable to watch. With its harsh industrial sound design and grating black-and-white visuals, it felt like an attack on the senses, but one that left me intrigued. It was only after watching Eraserhead that I realized film could well and truly be an art form.

From that point on, I watched as many Lynch movies as I could get my hands on, watching almost all of his amateur shorts and even going as far as to see the infamous spectacle that was Dune (unfortunately, even as a diehard Lynch fan, I can’t defend that one). To me David Lynch represented everything that movies can and should be. It is the standard from which we have fallen every passing decade. When I decided that I wanted to go to film school, it was because I wanted to revitalize the spirit that Lynch brought to his movies, a sense of absurdism and unabashed experimentation that I feel has been lost in modern filmmaking. So you can imagine how I felt when I learned that Lynch had died on the 15th of January this year, just a few short weeks ago. He was 78, but nonetheless, I felt like there was still so much more he could have given the film world but would now never be able to. I knew that I would never be able to see one of his movies in theaters unless it was an anniversary showing, because there were no more David Lynch movies to release. I still feel a little bit like I’ve been cheated out of something, but for now I’d like to focus on his legacy.

Lynch started his career as a painter at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, and has always viewed himself as a painter, rejecting the public’s desire to view him only as a director. As someone whose interest in visual media also started in the traditional arts, I appreciate the perspective he brought to films. Whenever I watched a Lynch movie I always had the sense that I was watching an artwork more than I was watching a movie. Lynch understood film as a fundamentally visual medium with properties unique from that of any other, and he exploited these properties the way only an artist can– focusing on the visual components of each shot and using them to establish tone just as much (if not more) as he used the dialogue itself. Visual content is not an aid for storytelling, it is the storytelling itself.

Lynch made his first short film in 1967 as an art student in Philadelphia (a city that he hated so much it inspired the themes of urban alienation in Eraserhead) – titled Six Figures Getting Sick. It was unique in its complete separation from any cinematic precedent. In fact, Lynch had not intended for the short to be film-like at all, instead, he described it as the product of his desire to create a “moving painting.” The camera focuses on a group of six painted figures whose sickness manifests as them vomiting, repeated on a loop. While at first it appears as a simple looping video, there are slight changes in the footage that make the viewer question. In the corner of the screen is a pulsating “Look,” that appears to transition to “sick” during the video. But whether this change really occurs or not is never fully clear, leaving a sense of uncertainty that stays with the viewer.

The surreal but tactile nature of Six Figures Getting Sick (1967) continued in his later shorts, like The Grandmother (1969) and The Alphabet (1969), and eventually became a staple of his filmmaking. Even from the very beginning of his life as a filmmaker there was a clear sense of the disturbing, a sort of profound uncanniness that lingers beneath the surface.

His first feature was Eraserhead (1977), a movie that took over four years to make because he had a crew of seven people and a budget entirely dependent on grant funding from the American Film Institute. Despite these constraints, Lynch was still dedicated to the project, perhaps because the themes were so personal. Following a man living in an urban wasteland, Eraserhead (1977) depicts the journey of a man who discovers that his girlfriend has given birth to a mutant child. While the premise sounds fantastical and unserious, at its core, Eraserhead (1977) is a movie about the suddenness of adulthood and its inescapable nature. For Lynch, who had just had a daughter and was three years way from divorce when the filming started, it’s likely that Eraserhead (1977) served as an abstracted way of processing the weight of the adult responsibility he had so recently taken on. When Eraserhead (1977) was released, it became an underground hit. The general consensus was along the lines of “I don’t know what this movie is doing but I know that it’s doing it well.”

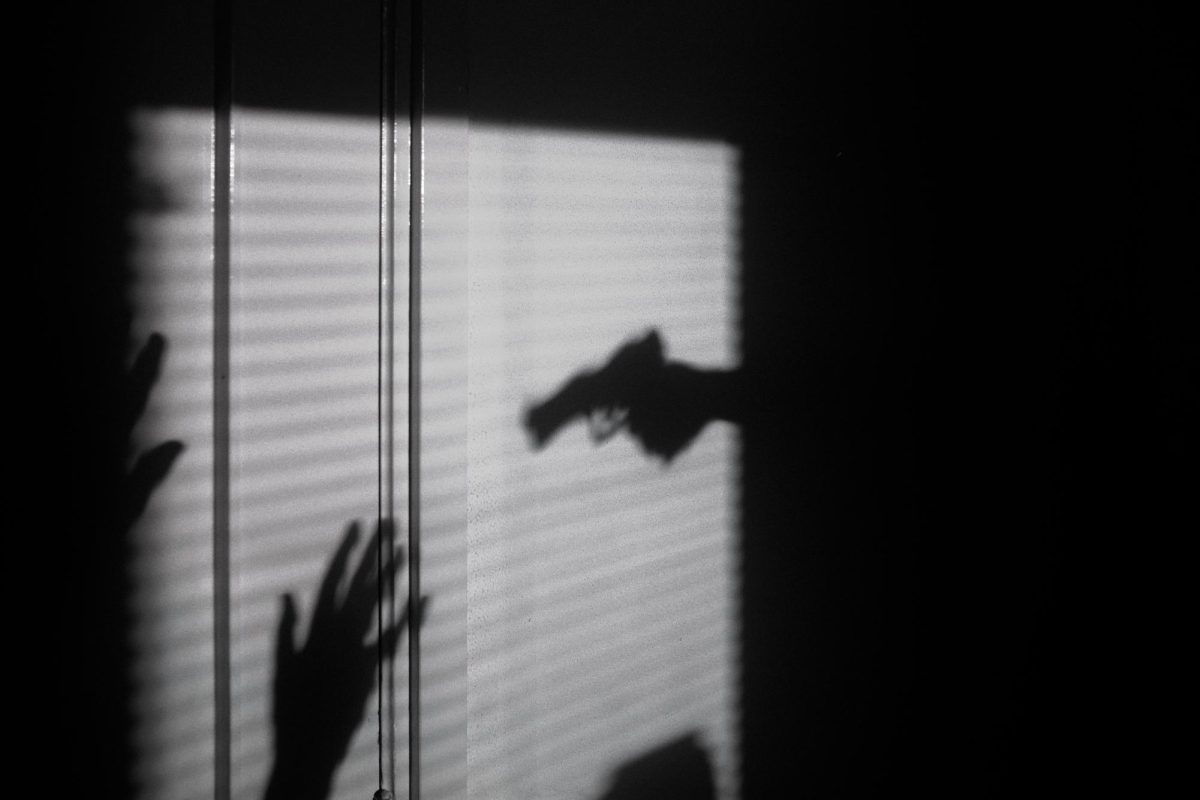

Supported by the success of Eraserhead (1977), Lynch went on to make critically acclaimed hits such as The Elephant Man (1980) and Blue Velvet (1986), never compromising on his distinctively surreal style. In 1990 he released Twin Peaks, a TV show following the mystery behind the death of young Laura Palmer in the titular rural Washington town. Twin Peaks was an anomaly in the sea of sitcoms that littered TV screens, garnering much attention from the public. It is also a masterful example of Lynch’s characterstic uncanniness put to use in a narrative. Laura Palmer is dead from the very first scene of Twin Peaks, but she is always present in the storyline. Through her old videos, her appearances in characters’ dreams, and her lingering absence, she is always haunting the narrative. This reinforces the show’s central theme of death as a fundamentally predetermined phenomenon. Laura Palmer is perhaps one of the greatest representations of absence as presence.

In 2001 he released Mulholland Drive, his most famous movie. One of the few arthouse films to break into the mainstream, Lynch received a best director nomination for the Oscars. A breathtaking vision of Hollywood as a perverse dreamscape, Mulholland Drive is a neo-noir mystery that has rightfully claimed the title as one of the best art films of the 21st century. If you’d like to see it I’d recommend watching Lynch’s Blue Velvet first as an introduction to his style with a similar neo-noir edge. His only movie after Mulholland Drive was Inland Empire, a reflection on the mind of a troubled actress, as played by regular collaborator Laura Dern.

Despite the moody and disturbing nature of his work, Lynch was generally considered to be a friendly and cheerful person. According to actors who worked with him, such as Laura Dern and Naomi Watts, he was always considerate of actors and never placed his work above their wellbeing. This is in stark contrast to other distinctive directors like Stanley Kubrick whose work always took precedence over all other aspects of their life. In the years before his passing, he had a Youtube channel called David Lynch Theatre where he frequently posted videos about his ideas and “weather reports,” where he’d give short updates about his life and make surreal comments about the weather in Los Angeles.

I’m sincerely grateful for Lynch’s contributions to filmmaking as someone interested in the same field. To me, his work represents a sort of inhibited creativity and dedication to style that I feel is essentially missing in modern filmmaking. But I hope that in the coming years the spirit he brought to his work will be revitalized. So if you’re tired of formulaic plots and want something with a little more edge– maybe Eraserhead will do the trick.