Can the female gaze truly exist?

The term “male gaze” was coined in 1975 by British cinema scholar Laura Mulvey to describe the objectification of women in Western media. The important question that is frequently asked is whether women can have an equal gaze. If men, both onscreen and as producers, held the active roles and rendered women the fetishized or punished objects of the gaze in traditional narrative cinema, could feminist filmmakers create a film space in which the roles were reversed? What about queer women viewers and people of color in an inherently heteronormative, white setting? Is it necessary for every spectator to be subject to the masculine gaze inside the pictures and narratives of a patriarchal culture?

Because the male gaze articulates the perspective of a male-dominated society, one solution to the question of the female gaze is that it does not and cannot exist because such a gaze would require the existence of a female-dominant culture in order to be theorized.

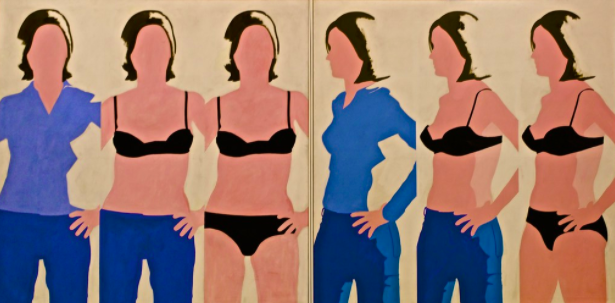

Alice Walker’s literary collection ”In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” includes a narrative about her mother’s television viewing experience, who worked as a maid but associated with the affluent white women of soap operas rather than their black workers. Such an example demonstrates how one might identify in accordance with a dominating gaze rather than oppositionally, even though it is politically in one’s best interests. The idea of an oppositional gaze is critical for investigating the race, class, gender, and sexual aspects of the patriarchally dominated gaze. If heterosexual women of color may watch films about race with a critical, rejecting eye, what happens when lesbians see heteronormative images and narrative? A queer woman’s gaze may offer identification with the male gaze in the desire for the female gaze’s object. For example, a lesbian, pansexual, or bisexual spectator may admire an attractive woman rather than want to be like her. This, however, would not aggressively confront the male gaze’s objectification of women. Furthermore, previous representations of lesbians have not challenged the gaze. Historically, lesbians has been reviled in film as either an anti-social monster or a mentally unstable creature who needs to be brought into the heterosexual fold by the appropriate guy. Even when the male gaze is not as obvious as it is in pornography, the fetishization of women’s bodies persists as a dominant visual technique.

Because of the cultural circumstances that have made the male gaze dominant, it is impossible to imagine reversing the look. For example, in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, a woman known only as “The Bride ” pursues vengeance on the squad of killers who betrayed her. This form of revenge narrative may provide brief pleasure to female viewers associating with the character. Despite the fact that the heroine is an assassin, which is a typically a male occupation, the fact that she was a wife and pregnant at the time when the tragedy that motivates her occured, highlights that her retribution is based on traditionally feminine values. Though women are often penalised for striving to gain masculine authority, male control in this situation influences all choices a woman makes. Despite this, The Bride’s aggressive, violent character does not prevent visual objectification, particularly in the initial section of the story. By having several closely framed fetishistic images of her blonde, fit, slender beauty, the actress is still objectified even as the character resists masculine power.

Similarly, turning males into sexual objects cannot overturn all societal conventions and are rarely positioned in narratives or as pictures in the same manner that women are. Most of the time, the sexualized male body is an active, powerful body, as the man is the focal point of the story. From James Bond to Magic Mike, the attractive male in mainstream movies is either domineering or strongly muscled, or both.

Such analysis ultimately reveals that the female gaze is rarely an oppositional corrective to the male gaze, even when feminist directors are at the helm. The female gaze is probably best described as an important position of resistance—for filmmakers and audience members alike.